As I start writing again, I am thinking a lot about my grandfather. My father’s father. He is the only other person in my family–actually on both sides of my family–who writes. Or wrote. He died many years ago. It’s out of the ordinary for me to think about him, honestly. It might sound cruel for me to say that. But I always sensed in him a deep unhappiness, and found him difficult to be around. He died of emphysema and his last years were hard–on him and on my family. But before that, when he was still able to get around, he wrote a column for his town’s paper. He also wrote little stories and essays that I believe just circulated in the family, maybe among some of his friends, and sat in boxes in the basement of their condo, where he wrote on a large computer.

He had a thin cloud of red hair. He had always been skinny as a rail, but I remember him as painfully frail. He was quick witted but quite cynical. I sensed an underlying bitterness and despair, concealed by jokes and aloofness. I think he created this predominant way of being in our family, even though none of us have the same source of trauma that it emerged from in him. Or I don’t know. Maybe that way of being is just in our DNA.

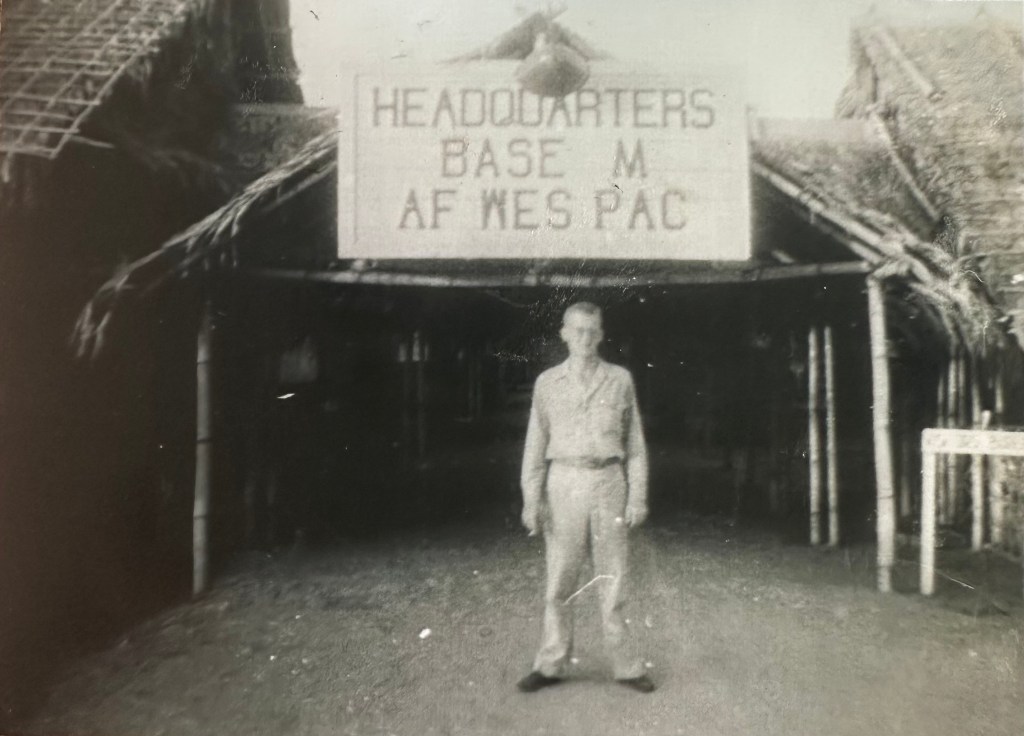

He served in the Philippines during World War II. He never talked about it. My dad and his siblings thought he’d worked in an Army office there as a clerk, and saw little to no combat. But lately, years after his death, I’ve been piecing things together through what has been left behind, and have discovered that this story is quite untrue. He fought in five “D-Day”-style battles (beach landings): at Lae and Finschhafen, Papua New Guinea; Hollandia (now Jayapura, Indonesia); and Leyte and Luzon, Philippines. At Leyte he was a “tech” in a unit that interrogated captured Japanese soldiers, and then turned them over to 41st Division, who “had a policy of take no prisoners.” “We didn’t follow up on that too closely,” he wrote. It seems that for the rest of his service (another year or so), he was stationed in Luzon. The only thing we know about that time is from a clipping we found from the local paper, saying that he was a “criminal investigator in the office of the Provost Marshal.” Intriguing and rather heartbreaking information.

I’ve been told that when he came home from the Pacific, he was dangerously thin and his teeth were all rotted out. He confessed to having nightmares and generally “a bad time.” His mother nursed him back to health, and then two years later he married a literal nurse, my grandmother. She took care of him after that, for 58 years. It was not easy. She was also someone who seemed to be a unhappy person underneath, trying to make the best of things but in real need of care herself, and unable to ask for it or seek it out. I know that he was grateful for her care, but he was also difficult and exacting, and they fought a lot.

This is a brief description of our other family writer. I know that I’ll write more about him at some point. Right now I am writing this to explore what writing means to me, through the context of my family. For my grandfather, it seems writing was an outlet to express himself but in a very limited, carefully controlled way. He did not write about things that haunted him. He wrote about golf, politics, marriage and family–and in a voice that was both jokey and aloof, that performed “I am a normal white middle-class man of the Midwest, and let me tell you some things about golf, and politics, and family.” The essay that I pulled most of the above information from is the only one I’ve seen with any detail about his war experiences. It wasn’t published, and I think that I am one of maybe 4 people who have read it. And even that essay glosses over so much, tells jokey anecdotes, and ends with the following statement, which I find emotionally gutting:

“There was very little of my time in the Army that was enjoyable.” (This after he’s filled nearly a page of a very short essay talking about celebrities he met during the war–as I said, jokey dissembling.) “Nearly 4 years of my life gone, with nothing to show for it but a lot of bad memories and a handful of ribbons. But as time passed, and most of the bad memories had been buried deeply, I began to realize I had benefitted by it. I had left home a teenager, not knowing much about anything, and I returned home a seasoned adult. … After two years of running around I married … built a home and raised 4 great kids. And was able to bury my war memories very deeply.”

I find this pronouncement to be emotionally dishonest and/or sadly un-self-aware, I admit. We know now that trauma just doesn’t work that way. And this stance represents the family culture I am resisting as I set out to write again: a belief in “burying” pain, of putting on a world-weary smile and a show of normalcy while slowly being eaten alive. When I was growing up, pain was something to be made fun of in others, and lied about to ourselves. My family rarely, and only secretly, admitted to pain in order to feel better or connect with others, to find support and fellowship in common experience. And it created harm. I know that it harmed me.

If my grandfather were still alive the first thing I’d ask would be, “Why didn’t you write about it? Like, really write about it?” But I already know the answer. It was terrifying to contemplate, let alone sit down and do. It would have been painful. And it would’ve necessitated being open with his family about his pain, and struggling through everything that came along with that. I understand that it was much easier to write about golf and my grandmother’s annoying love of ceramics. But I think it was also a loss. Our family, his friends, a wider readership, would have benefited from his truth telling. At least that is what I believe.

And it is what I tell myself now, confronting my own fears about truth telling. Yes, vulnerability and letting one’s self be known more deeply is a terrifying experience. I find that it is also difficult to maintain a sense of foundation, when it comes to representing “the self.” I don’t know if I really believe in a stable self. And finally there is the regret of wounding one’s family and friends, in the endeavor to speak experience, to uncover pain and regret. My grandfather obviously didn’t want his children to know about his war experiences when they were growing up, and then probably found it difficult to correct their knowledge later. Was this a kindness? Perhaps it was. It’s easier for me, more emotionally removed from him, to express a belief that he should have written more truthfully about his experience.

Michelle Tea, a famous memoirist, said in a recent interview that memoir writing is fundamentally a selfish act. It hurts people. If I continue writing more autobiography than anything else, I’m going to hurt people. Right now I confess that, like a typical self-involved person my attitude towards this knowledge is more, “Shrug. Sorry?” than anything else. Maybe I’ll feel more contrite after it’s done. But I don’t think I can not do it. I’ve always been self-involved–that is to say, focused mostly on what is going on inside my own head. (Because dude, it’s a lot.) It may be that I am just built neurologically for this type of writing. And maybe the people close to me will be able to look back and remember this about me, saying, “She was always going to do this. She has to speak her truth.” I can hope.

Anne Lamott says, “You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better.” I love you family, friends. And I will endeavor to always look for and represent your humanity. But I’m going to tell my stories.