It is first or second grade. I am asked to draw something that happened to me the previous weekend. We’re told to be creative with our drawings. I just hear, “Be creative.” I draw my family making brownies, which did happen, and a bear stopping by for a brownie, which did not. I’m proud of my drawing. But my teacher puts a frowny face on my drawing. I am confused. Then, later that day, I am terrified and ashamed when the teacher calls my mother at home to tell her what a horrible thing I’d done. Not only did I draw something that didn’t really happen, but when the teacher asked me for an explanation I’d doubled down and said that it actually happened. I had lied. The teacher and my mother were alarmed. To them, this was behavior to be nipped in the bud before it grew out of control. Before I became a liar. This was the first time that I was made to associate creativity with lying, and lying with shame. Or, put differently, to associate taking creative risks with rejection and reprimand.

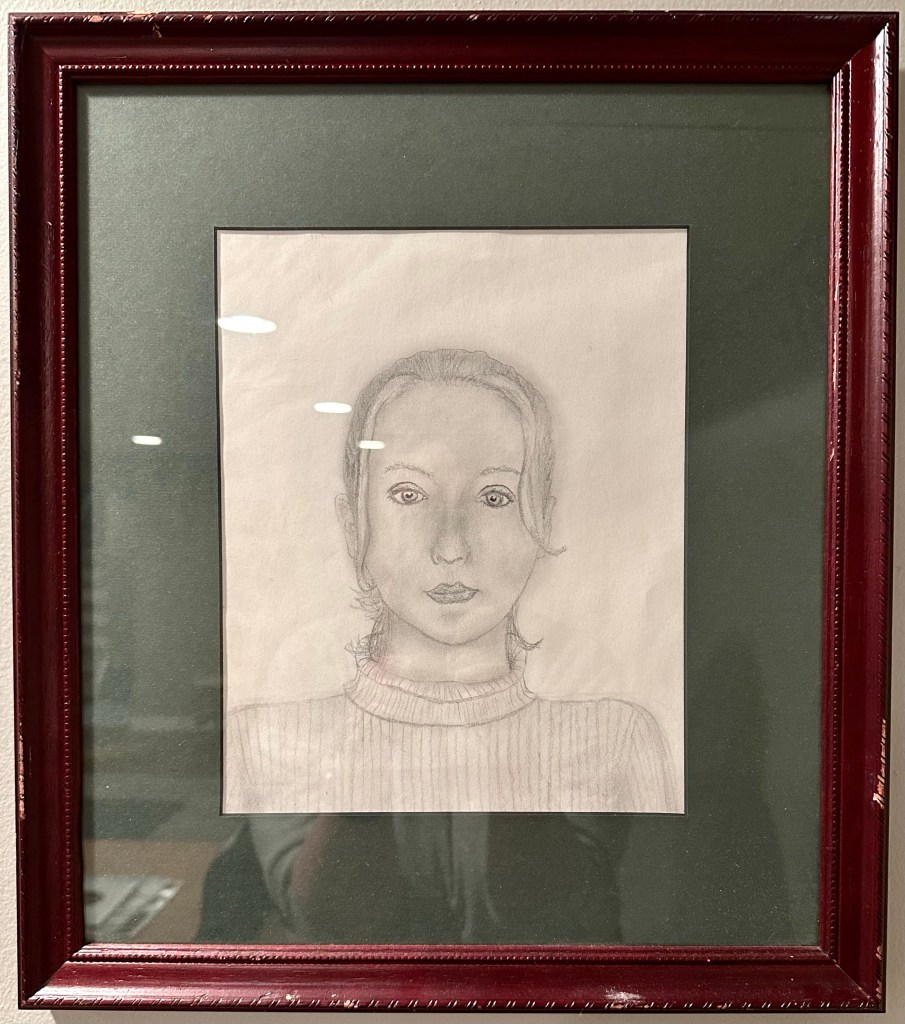

It is junior year of high school. I am taking an art class for the first time since elementary school, and I am loving it. I attack each assignment with excitement and purpose. My teacher likes my work. We are asked to draw a self portrait. I want to be taken seriously as an accurate drawer and produce a portrait that looks like me, but I am also 16 years old. I think that my face is misshapen, grotesque, ridiculous. I cannot bring myself to represent my monstrousness and then turn it in for all to see. I find myself instead drawing an idealized version: what I would look like if my face was narrow and symmetrical, with rosy cheeks and full lips, framed by wispy tendrils of hair and set upon a long neck. I turn it in. “This doesn’t look like you,” my teacher writes and gives me a low grade. I feel ashamed of my drawing and my face. I take the portrait home and try to hide it from my mother, but she sees it. Before I can explain what happened during my creative process, she says (and I remember exactly), “That’s a very optimistic version of you.” The shame cuts into me like a hot knife. I agree. I am not beautiful. I hide it somewhere and never look at it again. When the art class is over that year, I never draw again. 26 years later, my mother cleans out her basement and gives me a bunch of framed art wrapped together in a blanket, to see if I want any of it. I take it home, unwrap the art, and am stunned to find the self portrait in its midst. Framed. I am completely thrown, both at seeing it again and trying to understand my mother’s actions. Did she frame it because she actually liked it, and was clueless about the shame I’d felt? Or because she knew that she’d handled it badly and this was some kind of apology? I didn’t know, but I imagined smashing it. Burning it. Drowning it. Instead I hung it on the wall in an effort to reclaim it.

It is senior year of high school. Our beloved AP English teacher has given us an essay assignment with a creative spin on it. For this essay, we can adopt a pen name and try to write in a voice that is different from our own. I realize that I have been waiting for this moment. I am a creative writer, known in our grade for my poems and stories published in the school newspaper. I am secretly proud to be voted “best writer” of my class to an embarrassing degree. Generally I have found the book report/essay genre to be rather stifling. Here is my opportunity to turn it into a creative project! I am thrilled. This also happens to coincide with a time in my life when I am obsessed with the movie The English Patient, in a way that only a romantic neurodivergent 17 year-old can be. I choose Katherine Clifton, one of the characters, as my pen name. For the voice I’m going to adopt, I look to some volumes of poetry by Tennyson and Wordsworth that my grandfather had recently given me after downsizing his book collection. Their voices seem passionate and intelligent-sounding, a combination that I want to be. I write my essay. It is so much fun. But the teacher is one of the most popular teachers at our school. I desperately want to impress her. She hands back our essays. At the top of mine, in red ink, it says the following (I remember it exactly—even the sarcastic “scare quotes”):

“This is quite pretentious, stilted prose, ‘Katherine.'”

And there’s a B-. The lowest grade I’ve ever received on a writing assignment.

I feel like someone has shoved me down an elevator shaft. And completely baffled. Did I misunderstand the assignment? Why did it matter which voice I’d chosen, only that I’d used one? Hadn’t she said to experiment, be creative? What do “pretentious” and “stilted” even mean? I slink out of the room, mortified. I go home and look up the words. I burn them into my mind. The shame is so total, and I take the event so seriously, that it results in my decreeing to myself once and forevermore: “And so it shall be that from this day forth thy writing shall never be pretentious and stilted—on pain of death.” Every writing assignment from that day on is carefully reviewed for “showiness,” “proudness,” “self-satisfaction,” and “flowery language.” I sound like everyone else. Thank you, teacher. Lesson learned.

The next twenty five years of my life are profoundly shaped by these experiences and a hundred more like them: when I tried to express my creativity in some way, the grown-ups in my life reacted with shock, discomfort, confusion, and disdain. I go to college. I want to study creative writing, but I let my parents talk me into pursuing an English teaching degree instead. After my first year, with stone in throat, I am able to tell them I’ve moved on from this plan. But I can only bring myself to aim for “a career in publishing.” I am too terrified at that point to return to creative writing. I have fully accepted that I am a creative failure. I shift at a certain point to academia rather than publishing as the goal–still wanting to take creative writing courses “on the side,” but too terrified to do so. Terrified that it will only confirm my creative failure even more.

But in academia I learn about pedagogy. I start to realize how flawed and damaging my teachers’ and parents’ approaches to my creativity had been. I realize that it is more likely that their reactions were entirely about them and their experiences, and not about me at all. They were insecure and uncertain in the face of my creativity. They lacked the expertise I needed. If I’d had just one person in my life who could’ve taken me aside and said, “Do not listen to these people. They know nothing about what you’re doing and where you’re trying to go. Tune them out and do your thing until you find a community somewhere else.” But I didn’t. All the adults around me devalued creativity as a vocation and tried to caution me out of it at every opportunity they could. And it worked. They won.

For a long time. There was just one problem, though. The problem was the feeling, the one that never went away. Instead it just buried itself deep, and weathered its condemnation and abandonment. It waited until it sensed an opportunity, an opening. It was watching as I stepped off the academic treadmill with nothing but a desk job to focus on. Then it started whispering to me. And when I kept ignoring it, it started to yell.

“This isn’t our life!” it shouted. “What are you even doing? This isn’t what we’re here to do!” Without a lifestyle like academia to devote myself to, the absence of the life I was supposed to be living was suddenly the only thing in view. Gradually I had to admit that the feeling was correct, and that it was only fear that was stopping me. It felt like a feral, fangs-bared, snarling terror when I tried to circumnavigate it—but it was really only the fear and shame from my early experiences, that I had never confronted and allowed to fester.

I remember the moment, a couple years ago, when I first read the words “creativity scars.” It was a profound moment of culmination for me; my grappling with these memories had prepared me for the concept so that when I saw it, I instantly understood. I am not weak, broken, incapable, lazy, untalented or a failure. I am merely wounded. I have creative scar tissue. It is thick because it was trying to protect me in a harsh environment. But I am not a vulnerable child anymore. And I have created a safe environment for myself. It’s time for me to cut bravely through that scar tissue and explore what’s underneath.

I have enjoyed writing these posts, and they have done me so much good. I do feel, however, that I have been “pulling my punches” to a certain extent, and hiding in a voice and blog format that still feels pretty safe for me. It is time for me to start leaving my comfort zone with these posts, and take more creative and personal risks. Stay tuned.