When you were a kid and you stayed overnight at someone else’s house—a friend’s or aunt and uncle’s or grandparents’— you could never fall asleep right away. You would lay there trying, listening to everyone else go to bed, and the house would grow quiet. Then you would carefully get up and roam around. Or really, because you were trying to be quiet and not get caught, you would sneak around. You wanted to see what everything looked like in the dark. You wanted to look at things you didn’t feel comfortable looking at closely when everyone was awake. Especially with your friends and your cousins, you looked through their stuff. Their toys, their jewelry, school supplies, anything that was laying around. If something small and interesting caught your eye, something you didn’t think they’d miss, you took it. You tucked it in your bag, and it made you feel calmer. You’d usually stand or sit for a while in the dark living room, just listening to the sounds of the house. The refrigerator. The heat. Someone’s breathing. A car passing on the road. Eventually you would finally feel calm enough, and you would go back to your sleeping bag or cot or borrowed bed. You would curl up tight like a wild animal and fall asleep.

Author: MJ Sparling

Brain Bleed

Your grandfather has his first stroke in his fifties, before you are born. Your mother is in college. By the time of your first memories of him, he has likely had one or two more, but he is still quite functional. Your mother and aunt tell you that, as the oldest grandchild, you saw him at his best. An exacting, emotionally-volatile man, his strokes tempered him for awhile, and for your first few years he is silly and playful. He lets you paint his face. He teaches you to blow a bubble with gum. He holds your hands as you roller skate around the kitchen. He hulls strawberries with you on the back porch, while you sort the good from the bad. He builds you a wooden rocking horse, and a wood puzzle of your name. You build a snowman together. He makes you laugh. By the time of your sister and cousins’ first memories, however, he is more shut down, slow, even scary to them at times. Because you know him differently, he is never scary to you. Just sad.

For most of your life you are told that you take after your father’s mother, and her family. And largely that is true. You have her eyes, nose, gangly-ness, risk of colon cancer, depression, emotional sensitivity and cynicism. This narrative–mostly perpetuated by your mother–that everything about you comes from your father’s side is so predominant, that it never occurs to you that you could inherit the clotting disorder from your mother’s side. You take birth control with estrogen for decades with no issues, even have a doctor tell you you’ll never have to worry about blood clots. But then suddenly in your forty-second year you have two in your lungs and a cluster behind your left knee. You can’t breathe and your leg feels explosive. The doctors now say, “With your family history you never should have been on estrogen.” You roll your eyes. They take you off the estrogen and say, “You’ll be fine now, but here’s six months of blood thinners just in case.” At six months they do follow-up bloodwork to punctuate the end of the course, but it comes back showing your clotting factor even higher than when you had your “event.” “Huh,” they say.

Your family doesn’t really know how many strokes your grandfather had during his last twenty years or so. Each one chipped away a little more. He became mostly nonverbal and physically slow, but he never lost the ability to walk, to feed himself. He was on blood thinners for decades, and finally it was a brain hemorrhage that killed him. You wonder now at the strength and will that kept him alive and functional for so long, with so much brain damage. You wonder if you’ll be called upon to achieve the same feat, and you don’t believe you’re up to it.

Your whole life it has been intelligence that has defined you. Your mind. You knew you weren’t beautiful. You knew you weren’t selfless or devoted to others. (You knew these things because you were told, implicitly and explicitly, over and over again.) Intelligence was your gift, and anything good in your life that happened would have to be the result of intellectual discipline. When you ask your mother why she married your father she says, “I knew that no matter what, our children would be smart because his family was smart.” She was eighteen when they married, and he was twenty. But both of your parents are smart and both sides of your family are smart, relatively speaking. One side has a reserved, traditional version of intelligence. One side has a sarcastic, critical version of intelligence. But for both sides, a lack of intellectual curiosity or a perceived tendency to make “poor decisions” are treated as failures of character.

You realize now that this upbringing created in you a pathological need to be seen as intelligent. When anyone says anything to you that suggests they doubt your knowledge or judgment, you shift immediately into “fight” mode. You cannot stop yourself from correcting them, while putting them in their place besides. Even being asked if you’ve registered to vote feels like character assassination. “Of course I’m registered to vote,” you think. “Do they think I’m an idiot??” You’ve even managed to find yourself a niche career where you can excel by understanding–to a degree–all research. Literally all of it. It fills you with pride knowing that you are so intelligent that you can do this. Your parents couldn’t do it. Your mean, condescending school friends who thought they were so smart couldn’t do it. You bask in the knowledge that you are the smartest person you know; nothing else has the ability to make you so proud of yourself.

This is why the suddenly real possibility of stroke, of brain damage, is so shattering for you. Who are you without your steel-trap mind? Who are you without your pathological independence financially enabled by your intelligence? A person without mental acuity is a dependent. A burden on others. A sad case. One without a purpose, beyond a losing battle for survival. You realize you can’t need others in the ways this would necessitate, because doing so would be self-annihilating.

Your parents taught you one foundational lesson above all else: Learn how to take care of yourself, because no one else will. It takes you decades to see this lesson at a critical remove, to recognize its isolating and self-fulfilling logic, and the biographical implications it holds about your parents, their parents, and your generational inheritance. By the time you see it, buried deep within you, it feels like the fatal flaw in the keystone of your personhood. How many relationships in your life have you burned through like a wildfire, believing they were all too flimsy to survive? How would you even go about unlearning this stance towards others? Your parents are no models. Your romantic relationships have predominantly been people attempting to take care of you, and you being unable to accept and reciprocate. You have no trust in people at all. And no belief that you have a capacity to care for others. Because in a way, you don’t: you are fully responsible for taking care of yourself, and even at that you are a failure. The broken math in this equation is only now becoming clear to you.

Land of the Elk

You grow up in an unusual neighborhood, though you don’t know that at the time. A “resort community” they call it, but it is wooded, sparsely populated. Not all the roads are paved. Some roads only have one house on them, or none. The neighborhood is a labyrinth in the woods, clearly designed for a huge community that never materialized. Some of the houses are mansions owned by rich people from metro Detroit who barely visit them. Some of the houses are small dark A-frames with propane pigs in the back and husbands who smoke in the front yard sitting in plastic chairs. They named it “Michaywe,” supposedly an Indian word for “Land of the Elk”; you are in your twenties when you realize this is probably white corporate B.S. Plus, no elk.

When you are young though, the neighborhood is determined to grow. You remember exploring houses in the process of being built–still just studs, or just an uncovered basement of cinderblocks in the ground. The neighborhood at that time has a golf course, ski slopes, a pool, a lake with paddleboats, tennis courts, a playground, a restaurant with two banquet rooms, and summer programs for the neighborhood kids. Your father works for the golf course. Every Halloween and Christmas your family goes to parties in the upstairs restaurant banquet room, and you are taken around the golf course with the other children on hayrides and sleigh rides. Your family is a company family. Everyone in the neighborhood knows your dad. After a while you realize that many people don’t like your dad though. He’s not always an easy person to get along with. He’s always in a “dispute” with the HOA, for reasons you still don’t understand. Your mother is a preschool teacher, then sells ads for the local newspaper, and she is literally the most beautiful woman in town. Everyone knows your mother too. It takes you longer to realize that many people don’t understand your mother, and she doesn’t understand them. There’s some kind of disconnect. You idolize your parents though. They both act like they are very important people, and you believe them for a long time.

For you and your sister–white blonde girls from the company family–the neighborhood is your own personal forest reserve. Property lines mean very little to you. You know the miles of dirt trails that wind through the woods by heart. You know the best trees to climb in a one-mile radius. You know where the deer sleep, where there is an enormous boulder among the trees, where the blackberries grow, where dead trees have fallen onto each other and created balance beam matrixes. You know where there is a grove in the fall where you can wade waist-deep in yellow leaves, bright sun filtering down through the golden canopy. You snap wintergreen leaves in half and chew on them. You find a forgotten wooden cable spool in the woods. You find a dead deer with an arrow in it, but it’s not hunting season and you tell your dad.

You make forts all over the neighborhood, and visit them all. You bike home with hands sticky from pinesap, legs scraped from tree bark. Grasshoppers fly before you down the gravel road. It can be tricky riding a bike on those sand and gravel roads. One day you take the curve in front of your house too fast, the tires slide sideways over the gravel, and you hit the road chest-first–losing your breath and the belief you’ll never die. Eventually your road is paved with smooth, shockingly black asphalt, and you can make the loop with rollerblades again and again and again until it’s too dark to see.

The house you grow up in is very plain in the front–a completely flat two-story facade with wood siding. Your mother tries to dress it up a bit by painting it sage green and the front door eggplant purple. The back of the house, however, is ski-chalet style with two-story picture windows looking out into the woods. Your parents have the house built when you are five. The contractor builds a number of them throughout the neighborhood with the same floor plan, but the other homeowners have their windows face the street instead of the woods, which always puzzles you. The contractor is not great at his job. Within a few years there are leaking pouches of water in the walls upstairs, and in the basement your mother receives an electric shock every time she touches the dryer. Years later, your parents discover there is an empty space behind the upstairs bathroom that is completely uninsulated, unventilated, and causing roof rot. The woodpeckers love to gouge holes in the front of the house. All around the house there are trees mere feet away from it. You can reach out your bedroom window and touch a tree.

There is only one other house on your street; an old couple lives there. The street is U-shaped, with your house at the first curve. When you’re in bed at night and a car turns down your street, its headlights flood your room then slowly refract and slide away as the car passes the house. You are aware that no one should be driving down your street at night; it is always unsettling. In the summer the windows and back sliding door are left open with only the screens between you and the woods. It’s not so familiar then. Nocturnal animals sound like footsteps rustling through the dead leaves. Something catches a rabbit and it screams for its life. Owls hoot, toads croak, crickets drown everything out in waves. Your mother wonders why you struggle to sleep.

Some Thoughts on Oppenheimer

The convergence of the pandemic and rise of streaming media has been a disaster for movie theaters. For a variety of reasons, many people have stopped going to see new films in the theater and now wait until they are streaming. But this summer, two highly-anticipated films were released during the same weekend and became a synergistic event that offered a glimmer of hope for theaters, movie fans, Hollywood studios, and the vast labor force of those who make movies. In the weeks and even months leading up to “Barbenheimer,” the excitement for the weekend and its films grew and grew. The early reviews of both films were glowing, and many, many people got caught up in the anticipation and all of the memes, filmmaker interviews, Tik Tok videos, and pre-release think-pieces. Thus, it didn’t really come as a surprise that the early box office returns for both films were strong, even beyond what experts had anticipated. There was a feeling, for those of us swept up in the moment, that something increasingly rare was about to happen: a communal cultural event. And because the emotions this event created in people were so strong (feelings no doubt stemming from this moment’s many socio-cultural-political-ecological conditions, in addition to the nostalgia of both films), it is also no surprise that both have seemed to become more than themselves. “Christopher Nolan’s Masterpiece,” was one of the headlines I read in the days before I saw Oppenheimer–and based on everything I had seen and experienced online, I went into the film expecting not much less than that. I would have done well to step back, see the moment for what it was, and temper my expectations.

I believe that when this moment has passed, Oppenheimer will be seen for what it really is: an old-fashioned movie about a sprawling group of mostly white, dismayingly-myopic men racing to solve a scientific problem before the enemy does; then the film concludes with a patent gesture toward the consequences of their actions–a gesture that mostly falls flat because the narrative until that point, by focusing closely on these and only these characters, has inevitably made them sympathetic, even, as is the case here, heroes or martyrs or saints. The viewer is either unfamiliar or painfully familiar with the depth and nuance of the consequences that are not being captured; if the former, the film seems like a decent film, and if the latter, the film feels unintentionally gut-wrenching and dismayingly narrow and irresponsible. Even from among the long list of predecessors to Oppenheimer in this genre of “important men of history racing to solve problems they themselves are creating,” the film is not able to innovate much or even cohere into a solid offering. It is two movies crammed together–or really, an exciting scientific method action film unsure of how to portray its tragic underbelly, that suffers from the weight of an additional, labyrinthian dual-trial film breaking its back.

The film does look amazing, and there are scenes that are extremely effective in what they are trying to do. The lead actors deliver incredible performances, even if–as is the case particularly with the female leads–they are given nothing of substance to inhabit. Florence Pugh, one of the best actresses working today, is cast almost solely to be naked and then to commit suicide at the ideal narrative moment to wrench maximum anguish from the protagonist. Emily Blunt, also wasted here, is the broken yet devoted wife of the brilliant man. There is also a young, plucky female scientist on Oppenheimer’s team, but–plot twist!–she has opinions and doesn’t always agree with the way the Manhattan Project functions. The rest of the cast is a punishing avalanche of every white male actor working in Hollywood today. As they fall and fall on you, one can’t help but be pulled out of the film and think of how each of them must’ve celebrated being cast in the brilliant auteur’s latest offering. I love Cillian Murphy most ardently, and he is fantastic here; if not for Peaky Blinders this would be the performance of his career. But the film consistently does him a disservice in failing to explain the motivations of his character. J. Robert Oppenheimer drifts through the events of the film like an embodied narrative device, seemingly filled with emotion but with no apparent well of experience he is drawing from. The film expects you to bring your own understanding of what his motivations may have been, and your own understanding of the historical moment he was reacting to–but in an era when fascism is again on the rise that feels like a mistake. The film contains insufficient gestures of acknowledgement toward the native people of New Mexico, the Japanese civilians affected by the bombs, and the American citizens exposed to radiation in Trinity’s vast fallout zone.

Finally, the part of the film focusing on the cabinet confirmation hearing for Lewis Strauss, played by Robert Downey Jr., just didn’t work for me. The snappy, all-expository dialogue felt clumsy and mismatched to the rest of the film’s dialogue style (at one point I thought to myself, “Did Aaron Sorkin write this part of the script?”), and the reveal of Strauss as “the” villain felt forced. There are plenty of villains here. The devotion of the film’s attention to this part of the story felt misguided. In a movie called Oppenheimer, I would rather that time be spent more closely focused on its supposedly enigmatic protagonist: exploring his motivations, his ethical and political struggles with members of his own scientific community, and his last act as a vocal opponent of weapons of mass destruction. Or the movie could’ve been called “Trinity,” and been a different movie. Or the film could’ve been almost entirely focused on the “kangaroo court” hearing about Oppenheimer’s security clearance, a play-like script in a cramped, sweaty room, employing flashbacks for dramatic effect. Instead Nolan tries to have the movie be all these things and more, and it can’t hold its shape.

I haven’t seen Barbie yet, but I anticipate that I’ll like it better–which is not what I anticipated a few days ago. I’m a “serious movie” person at heart; but this serious movie didn’t work for me. I don’t believe it will be considered Nolan’s “masterpiece” (whatever that is), and think it will likely be remembered more for its “Barbenheimer” context than anything else. If you want to revisit Nolan’s great films, for my money they are: 1) Dunkirk, 2) Memento, 3) The Prestige, and 4) Inception. I would put all of those movies in front of Oppenheimer in terms of their influence on subsequent films and their unified vision.

The Watcher

I grew up in a two-story house with floor-to-roof picture windows on one side. Thankfully that side faced the woods, or anything in our house that didn’t take place in a bedroom or bathroom would have been visible to anyone who happened down our road. Nonetheless, it still gave me the feeling of living in a fishbowl. There was a two-track trail about twenty-five yards or so back, and occasionally a nondescript white van or white truck would slowly drive down it and past our giant windows. In those days, utility vehicles didn’t necessarily have logos or information on them. They just looked like vehicles. There were two small utility sheds on the two track about forty yards or so down the trail from our house, and I was told the vehicles were driven by utility workers headed to the sheds to do regular maintenance. There were occasionally walkers and runners and snowmobilers that passed by on the trail too. It wasn’t heavily used, but I noticed them all and watched to see if they were looking in at us.

At some point in my childhood, maybe around third grade, I started to become a very self conscious child. I felt deeply misunderstood and criticized by my family, friends, and classmates. I was made to feel that I was wrong–in what I said and did, in how I behaved and thought–and that I needed to correct myself. After what felt like many failures, I developed a strategy and even a total mindset shift–that I can see now was influenced by the fishbowl-like nature of my house. I began to pretend that someone was watching me. Always. Whether I was with people or alone–but especially when I was alone–a presence of some kind was watching me. They would see if my performance slipped. They would see if I acted strangely. The watcher was an observational but also evaluative presence. I felt I needed a watcher to remind myself at all times that my instinctual way of behaving was something I needed to overcome, outgrow. And the watcher’s presence kept me “honest,” kept me focused on transforming myself moment by moment into a normal person. But the watcher wasn’t one of my parents or friends–this, now, seems key. I would never actually encounter the watcher and receive their feedback directly. Instead I would see myself through their eyes and know the feedback inside. I would take judgment supposedly external and internalize it, so that it didn’t feel like painful, embarrassing external criticism. It felt more like consensual self-transformation.

If this sounds kinda creepy, well yeah it was. The watcher was the creation of a self-conscious, scared, lonely, imaginative kid. I needed the watcher to be a little creepy, to remind me what the stakes were. This was not a game. I had to become normal. But the watcher wasn’t only creepy or scary. The watcher was also comforting. At times the watcher was the only constant and engaged presence I felt in my life. My parents were busy, distant. My sister was three years younger than me. My friends were so different from me. The watcher understood me, was the only one trying to help me. Or at least, it was the kind of help I imagined that I needed. And it was a presence that became total: I felt like/imagined I was being watched every moment of every day: when I got ready for school, when I walked to the bus stop, while I rode the bus, during the school day, on the bus ride home, in the store, at the pool, in the woods playing, on vacation, eating dinner with my family, while I got ready for bed, while I tried to fall asleep. The observing presence was always there, motivating my performance. “Remember,” I would always think, “you are being watched.”

(While I don’t know a lot about child developmental psychology, I know enough to know that I am describing my own experience with a common developmental stage here. Just for the record. Some readers may have experienced something very similar, while others may not have. Oh, and if all of this makes you think of Foucault–yeah, that’s not lost on me either.)

As I grew up the watcher evolved. As my girl friends became interested in boys, and I wanted to keep up with them, and wanted to be liked by boys, the watcher developed more of a male gender–instead of the relatively genderless presence it had been before. I turned it into a presence that was interested in me “in that way”: as long as I acted a certain way, paid attention to my hair, learned how to hold my face in expressions that I thought were “attractive,” move my body more gracefully, dress and pose as if someone who might be interested in me was constantly watching. This was all an attempt to deeply engrain these behaviors and habits in me so that they became natural, so that I became an attractive and likeable person who didn’t have to try, perform anymore. And as I became interested in certain boys, the watcher became those boys. Or it was a boy I didn’t know yet who was obsessively watching me, in a way that was exciting and romantic instead of creepy.

Because our house was fairly remote, we didn’t always lock the doors. And in the summer we slept with all the windows and the back door open. I would lay awake on those summer nights hearing every rustle of dead leaves on the forest floor, hearing every twig snap and every insect fly past or bump against my window screen. I would imagine that I heard the back screen door slowly sliding along its track and someone entering the house. I could hear their soft, careful footfalls as they crossed the living room toward the staircase, and climbed the stairs to my upstairs bedroom. I could even look over to the doorway on my left and see a shadow hovering, lurking just outside my room at the top of the stairs. I would be filled with terror that my watcher was finally here to kill me. I had been wrong about him all along, and now I was going to learn that he had been biding his time, waiting to strike, and it was now. Now my watcher was going to kill me. But the longer I lay there waiting, watching the shadow in the doorway, the safer I felt. I became assured that no, he wasn’t going to hurt me. He just wanted to be closer. And I would fall asleep.

I took my watcher to college with me. I continued to feel a constant observing presence as I became an independent adult, taking classes, walking or biking around campus, watching free movies in the math building with other students, eating in the dining hall, studying in the library, laying and reading a book under a tree. I think in those years my watcher did start becoming less severe, as classmates and friends came and went and the stakes of “fitting in” eased a bit. Now the watcher was becoming more like an observing presence on the periphery of my awareness, without a strong pedagogical purpose. Don’t get me wrong: it could still be a disappointed or sneering presence exuding criticism of me during and after every embarrassing social situation or personal failure. And it was the rapist waiting in the trees when I found myself walking alone on campus after dark. But more often it was just an unknown-as-yet person I imagined watching me with romantic interest in a class or elsewhere, or an externalized presence helpfully reminding me to act like a normal person during this conversation or this class presentation.

[PhD school, resurgence of watcher during times of social and psychological duress, need]

In my 40s, I still feel my watcher. Maybe I always will–but I hope that I don’t. I know that he (yes, still primarily a gendered “he”) is a key part of the neurotic psychological apparatus that keeps me from overcoming my inhibitions, my self consciousness and self hatred. The reason I am writing about this today is that earlier I was lap swimming at my gym. As you can probably anticipate/understand, I feel my watcher quite strongly at the gym. Like a lot of people, I am extremely self conscious at the gym–and this is something I am really trying to work on lately, because for the first time in my life I have a gym that I really enjoy otherwise. It’s a gorgeous gym, and I can see it becoming a real sanctuary for me–if I can just get over myself. So today I was lap swimming and having a common, everyday realization that I have: that my awareness of the watcher was distracting me from being in my body and enjoying the really pleasant, comforting, and fun experience that I was having. Instead of feeling my body swimming, my attention was focused on the windows above me where the walkers on the indoor track can see the pool. “What does my freestyle look like from above? Is someone up there watching me, evaluating me, criticizing me, laughing at me, noticing that I’m not kicking hard enough, thinking that my arms aren’t extended enough when my hands enter the water, or that my hands don’t enter the water at just the right angle?” This is how the sensation of the watcher keeps me outside my body, outside my experience, and in a constant state of self judgment and self consciousness. This version of the watcher is not helpful for me.

And is there any version of the watcher that is helpful for me, really? I tell myself that it keeps me vigilant in terms of my personal safety–maintaining an awareness throughout the day that someone could be watching me through the windows, tracking my movements and my schedule, and planning to harm me. Sometimes the watcher is a fantasy about someone showing up at my door with a declaration of love, and it comforts me. I am lonely in a sense, but that loneliness is complex. I both do and do not want other people in my life. Part of me wants to be loved by a specific, amazing person, and the other part really wants to be left alone. But I’m never alone. I have my watcher. And sometimes that feels comforting and sometimes it feels stifling, creepy, oppressive. It’s both, ever shifting back and forth. I wish that I could feel blissfully alone when I want to be alone, and feel connected in some way to people when I feel lonely, without turning that feeling into a neurotic manifestation of a watcher.

Because of the way that I grew up, the house I grew up in, I feel most comfortable with a lot of natural light in my house–which means that the windows are all bare of covering during the day, and during the night only a few important ones are covered. I feel oppressed not being able to see out of my windows. But this also means that I am constantly aware of both what I can see outside and what people outside can see inside my house. Sometimes I worry that my childhood home turned me into a bit of an exhibitionist, someone who has a subconscious need to be watched from outside of their home. Someone who really wants to be seen by someone–as long as the observer stays outside, and keeps their feelings to themselves.

[What my attention-seeking behavior became when suppressed; but also sometimes self-care externalized]

Creativity Scars

It is first or second grade. I am asked to draw something that happened to me the previous weekend. We’re told to be creative with our drawings. I just hear, “Be creative.” I draw my family making brownies, which did happen, and a bear stopping by for a brownie, which did not. I’m proud of my drawing. But my teacher puts a frowny face on my drawing. I am confused. Then, later that day, I am terrified and ashamed when the teacher calls my mother at home to tell her what a horrible thing I’d done. Not only did I draw something that didn’t really happen, but when the teacher asked me for an explanation I’d doubled down and said that it actually happened. I had lied. The teacher and my mother were alarmed. To them, this was behavior to be nipped in the bud before it grew out of control. Before I became a liar. This was the first time that I was made to associate creativity with lying, and lying with shame. Or, put differently, to associate taking creative risks with rejection and reprimand.

It is junior year of high school. I am taking an art class for the first time since elementary school, and I am loving it. I attack each assignment with excitement and purpose. My teacher likes my work. We are asked to draw a self portrait. I want to be taken seriously as an accurate drawer and produce a portrait that looks like me, but I am also 16 years old. I think that my face is misshapen, grotesque, ridiculous. I cannot bring myself to represent my monstrousness and then turn it in for all to see. I find myself instead drawing an idealized version: what I would look like if my face was narrow and symmetrical, with rosy cheeks and full lips, framed by wispy tendrils of hair and set upon a long neck. I turn it in. “This doesn’t look like you,” my teacher writes and gives me a low grade. I feel ashamed of my drawing and my face. I take the portrait home and try to hide it from my mother, but she sees it. Before I can explain what happened during my creative process, she says (and I remember exactly), “That’s a very optimistic version of you.” The shame cuts into me like a hot knife. I agree. I am not beautiful. I hide it somewhere and never look at it again. When the art class is over that year, I never draw again. 26 years later, my mother cleans out her basement and gives me a bunch of framed art wrapped together in a blanket, to see if I want any of it. I take it home, unwrap the art, and am stunned to find the self portrait in its midst. Framed. I am completely thrown, both at seeing it again and trying to understand my mother’s actions. Did she frame it because she actually liked it, and was clueless about the shame I’d felt? Or because she knew that she’d handled it badly and this was some kind of apology? I didn’t know, but I imagined smashing it. Burning it. Drowning it. Instead I hung it on the wall in an effort to reclaim it.

It is senior year of high school. Our beloved AP English teacher has given us an essay assignment with a creative spin on it. For this essay, we can adopt a pen name and try to write in a voice that is different from our own. I realize that I have been waiting for this moment. I am a creative writer, known in our grade for my poems and stories published in the school newspaper. I am secretly proud to be voted “best writer” of my class to an embarrassing degree. Generally I have found the book report/essay genre to be rather stifling. Here is my opportunity to turn it into a creative project! I am thrilled. This also happens to coincide with a time in my life when I am obsessed with the movie The English Patient, in a way that only a romantic neurodivergent 17 year-old can be. I choose Katherine Clifton, one of the characters, as my pen name. For the voice I’m going to adopt, I look to some volumes of poetry by Tennyson and Wordsworth that my grandfather had recently given me after downsizing his book collection. Their voices seem passionate and intelligent-sounding, a combination that I want to be. I write my essay. It is so much fun. But the teacher is one of the most popular teachers at our school. I desperately want to impress her. She hands back our essays. At the top of mine, in red ink, it says the following (I remember it exactly—even the sarcastic “scare quotes”):

“This is quite pretentious, stilted prose, ‘Katherine.'”

And there’s a B-. The lowest grade I’ve ever received on a writing assignment.

I feel like someone has shoved me down an elevator shaft. And completely baffled. Did I misunderstand the assignment? Why did it matter which voice I’d chosen, only that I’d used one? Hadn’t she said to experiment, be creative? What do “pretentious” and “stilted” even mean? I slink out of the room, mortified. I go home and look up the words. I burn them into my mind. The shame is so total, and I take the event so seriously, that it results in my decreeing to myself once and forevermore: “And so it shall be that from this day forth thy writing shall never be pretentious and stilted—on pain of death.” Every writing assignment from that day on is carefully reviewed for “showiness,” “proudness,” “self-satisfaction,” and “flowery language.” I sound like everyone else. Thank you, teacher. Lesson learned.

The next twenty five years of my life are profoundly shaped by these experiences and a hundred more like them: when I tried to express my creativity in some way, the grown-ups in my life reacted with shock, discomfort, confusion, and disdain. I go to college. I want to study creative writing, but I let my parents talk me into pursuing an English teaching degree instead. After my first year, with stone in throat, I am able to tell them I’ve moved on from this plan. But I can only bring myself to aim for “a career in publishing.” I am too terrified at that point to return to creative writing. I have fully accepted that I am a creative failure. I shift at a certain point to academia rather than publishing as the goal–still wanting to take creative writing courses “on the side,” but too terrified to do so. Terrified that it will only confirm my creative failure even more.

But in academia I learn about pedagogy. I start to realize how flawed and damaging my teachers’ and parents’ approaches to my creativity had been. I realize that it is more likely that their reactions were entirely about them and their experiences, and not about me at all. They were insecure and uncertain in the face of my creativity. They lacked the expertise I needed. If I’d had just one person in my life who could’ve taken me aside and said, “Do not listen to these people. They know nothing about what you’re doing and where you’re trying to go. Tune them out and do your thing until you find a community somewhere else.” But I didn’t. All the adults around me devalued creativity as a vocation and tried to caution me out of it at every opportunity they could. And it worked. They won.

For a long time. There was just one problem, though. The problem was the feeling, the one that never went away. Instead it just buried itself deep, and weathered its condemnation and abandonment. It waited until it sensed an opportunity, an opening. It was watching as I stepped off the academic treadmill with nothing but a desk job to focus on. Then it started whispering to me. And when I kept ignoring it, it started to yell.

“This isn’t our life!” it shouted. “What are you even doing? This isn’t what we’re here to do!” Without a lifestyle like academia to devote myself to, the absence of the life I was supposed to be living was suddenly the only thing in view. Gradually I had to admit that the feeling was correct, and that it was only fear that was stopping me. It felt like a feral, fangs-bared, snarling terror when I tried to circumnavigate it—but it was really only the fear and shame from my early experiences, that I had never confronted and allowed to fester.

I remember the moment, a couple years ago, when I first read the words “creativity scars.” It was a profound moment of culmination for me; my grappling with these memories had prepared me for the concept so that when I saw it, I instantly understood. I am not weak, broken, incapable, lazy, untalented or a failure. I am merely wounded. I have creative scar tissue. It is thick because it was trying to protect me in a harsh environment. But I am not a vulnerable child anymore. And I have created a safe environment for myself. It’s time for me to cut bravely through that scar tissue and explore what’s underneath.

I have enjoyed writing these posts, and they have done me so much good. I do feel, however, that I have been “pulling my punches” to a certain extent, and hiding in a voice and blog format that still feels pretty safe for me. It is time for me to start leaving my comfort zone with these posts, and take more creative and personal risks. Stay tuned.

The Ice Cream Years

This post discusses disordered eating.

I’ve reached the age when my medical chart is starting to collect a fair number of conditions and disorders. Some of them are disruptive to my life, others not as much. But one condition was added to my chart in the last couple months that was quite a shock to me when I saw it. Earlier that day I had discussed with my psychiatrist my altered eating habits during the pandemic. A couple hours later, my After Visit Summary arrived and there it was in my list of conditions: “binge eating.”

I think I recoiled from my screen. No, I thought. That is not what I told her. I’m just eating a lot of ice cream. A few months into the pandemic, when I thought that maybe civilization was about to collapse, I had what I considered to be an epiphany: If I’m going to die or if civilization is going up in flames, I’m at least going to eat as much ice cream as I want in the meantime. And so I did. I didn’t imagine this–the ice cream eating and the pandemic–would continue for the next three years. But it has. There have been phases where I’ve restricted ice cream to about once a week, and phases where I have it almost every day. It comforts me. It’s a reward for making it through the week, or day. This is what I’d told the doctor. What she heard me describe was binge eating.

Yes, I did gain nearly 50 pounds in that first year of the pandemic, and it has not budged in the last two years. Yes, there are times when I worry about what the ice cream is doing to my body. I know it’s not “healthy.” I was raised around nominally “healthy” eating practices. I’ve been through nutritionist counseling. I’ve read Health at Every Size. I’ve read about Intuitive Eating. For the past three years, eating ice cream has felt intuitive!

I grew up in an environment of food restrictions. We did not have the foods at home that my friends had. We were not really allowed to snack, because it was “unhealthy,” and I remember long desperate waits until the next meal. Occasionally we’d go on fad diets like the vegetable soup diet. Any kind of fat and refined sugar were very bad. But I loved ice cream. I would often tell myself, “When I’m an adult, I’m going to eat as much ice cream as I want.” That was literally the main thing I looked forward to. Back then ice cream was a rare treat. My mother would get out the little bowls and give us a single scoop. I would practice self-restraint, and wait until it softened and I could stir it into a smooth consistency and spoon it up. I called it my “medicine.” It was always a moment of pleasure when the world around me fell away, and I would kind of fall back into my body and feel whole. And then I would be scraping the bowl with my spoon, and the world would rush back in.

I remember when Ben & Jerry’s was first stocked in our small town grocery store. My parents brought it home as a treat, but would only let us have a small scoop at a time. “It’s too rich,” they explained. In high school, when I could borrow the car, I would buy a pint on the way home from school or work and sneak it into the chest freezer in the basement, hiding it underneath bags of frozen vegetables. After everyone went to bed I would sneak it into my room and consume the entire thing in a state of rapture. I’d wrap the empty container in paper towel and put it in my backpack, to discard somewhere away from the house. When I went to college, I would buy pints from the store in the basement of my dormitory, and keep them in the minifridge freezer in our room. But I was broke and gaining weight, so I tried to exercise self-restraint. I forced myself to develop the habit of only eating half at a time, and the practice of walking very quickly past the store’s freezer to avoid the temptation.

Then the year after I graduated from college I got very sick–the sickest I’ve ever been. I couldn’t keep any food in my body for nearly a month. They never figured out what it was, but now I think it was just my first and worst (to date) severe IBS attack. But the lack of explanation at the time really freaked me out, and caused me to radically experiment with dietary restrictions, so that it would never happen again. (It had to be food’s fault, and food restriction had to be the solution. Right?) I tried all the fad diets at that time, tapping into reserves of willpower I have rarely seen again. I restricted dairy, among other things, for a long time after this. Ice cream was forbidden; only a breakup or severe PMS could cause me to “slip.”

I went to graduate school a few years later at a highly-ranked program in California. Everyone was thin and wealthy, and ate like birds. I fell in unrequited love with one of them, whose “type” was skinny. I lost a lot of weight trying to fit in. My Midwestern body type was so out of place: my relatively wide hips and shoulders, my round arms, my fleshiness. I got a CSA share and tried to only eat vegetables, lean proteins, and very dark chocolate with little sugar content. But no matter how much weight I lost, it didn’t work. I was never going to be one of them–the East and West Coast Elites. I had obesity in my DNA, and it was happy to bide its time while I experimented with starving myself. I gave in. I got a “normal” boyfriend with two sons, and we ate like a “normal” American family. Processed meats and side dishes out of boxes, cheesy Mexican food and seasonally appropriate desserts. My weight crept back up.

Then the pandemic. The vow to eat whatever I wanted to eat, because Screw It. 50 pounds. Therapy. A “binge eating” diagnosis. She has even started talking about my ice cream eating as an “addiction.” I have very conflicted feelings about this.

Part of me agrees with her. But is this the same part of me that hates my body, wants to control it, feels aligned with and has internalized our cultural fatphobia ? Or is it the part of me that wants to be healthy and survive? Could it be both at the same time? How do I separate them? I really can’t tell. And then there’s the third voice. The one shouting:

Fuck. Them. All.

Eat. The. Ice. Cream.

Find pleasure where you can, and don’t overthink it. Some day you will die. Until then, eat the ice cream and feel happy.

I have a lot of body dysmorphia with this new 50 pounds. The body I’m used to having, the body I imagine or even see when I look down, doesn’t match the body I see reflected back at me in windows, photos, mirrors. When I see it I always think, “My worst nightmare was to have a body like this.” For the longest time in my family, I was the thin one. I believed that I would always be the thin one. And I admit that I was smug about this. I felt both superior and relieved that I had dodged the obesity gene. But that “privilege” has been eclipsed by the inevitability of aging and genetics. I also hadn’t realized how much I was starving myself in order to hold onto that “honor,” and that this method would have diminishing returns. Maybe the ice cream “binge,” in addition to coping, was also a semi-conscious hastening of what I knew deep down was inevitable. The body I have now is closer to the body I’m supposed to have. I’m just not used to it, because I’ve been going to extremes to prevent its existence.

I don’t know what to do about the ice cream. Moderation, combined with healthy behaviors in other areas, seems rational. I confess that I know very little about binge eating; my biases and assumptions about it are entirely derived from social norms and pop culture. I imagine it as something very extreme, that takes you over, and not as someone sitting down with a treat at the end of the day, always the same amount, a seeming habit and not an uncontrolled mania. But maybe “binge eating” encompasses my behavior as well. Maybe, like many things, it’s a spectrum of behaviors.

Or maybe my doctor is just wrong. Maybe my behavior is a healthy response to present conditions and my past–and pathologizing it only serves to reinforce my shame. In eating what I want, I really felt like I was healing old wounds and making progress with my relationship to food, and not lapsing into just another kind of disordered eating. As long as I am paying attention to what I am doing and why, and endeavoring as much as possible to do what is helpful and nourishing to me, how could I really go wrong? If this results in a large body, my job is to accept and love that body, and ignore everyone who might be made uncomfortable by that body. Even if that includes (which it often does) my doctors. Because the reality is, they are uneducated and untrained about the science and treatment of obesity, and just as susceptible to fatphobia as the rest of us.

Recently a new, different doctor told me in a lab results message: “I recommend losing 10% of your body weight in the next few months, and then we’ll retest and reevaluate your lab numbers.” Everything I’ve read about the science of weight loss, and how completely unhealthy doing something like this is, led me to laugh out loud. I responded and explained that not only was that advice completely unrealistic, it was actually a very dangerous recommendation–based on the science of weight loss. (She also didn’t know, and clearly hadn’t looked into, whether my medical chart mentioned a family history of disordered eating.) Losing that much body weight in such a short amount of time would require near starvation, and would only result in my body going into famine-mode and dropping my metabolism down into the basement to keep me alive. If I didn’t become seriously ill and/or anorexic, I would not only gain the weight back, I would likely gain back more than what I’d lost. This has been proven time and time again in the research. She responded, “Don’t pay attention to the science, it’s too depressing! If you have the right attitude, you can do it!” **facepalm** I didn’t respond, and I don’t plan to discuss it with her anymore. If she brings it up again, I will likely cut her off and say, “I’m not going to do something so unhealthy, you shouldn’t advise your patients to do something so unhealthy, and we are not going to talk about it again until you are properly educated.”

I could write so much more about this. Obesity is such a focus of medicine and the media right now, particularly in relation to children, and this really scares me. I worry about how doctors, and we as a society, are approaching something we’ve decided is a problem with outdated, misguided, and ultimately very harmful beliefs about obesity. Obesity is not a personal failing. Obesity is most often genetic, or stems from environmental factors. Obesity is not even unhealthy much of the time. Most people in the “obese” category have very positive indicators of health. There are more negative health indicators associated with being underweight than being “overweight.” Why isn’t there a national outcry over underweight children? Because we hate fatness. Children should be protected from our ignorant and harmful beliefs about body weight. I know what it’s like to have your enjoyment of food hijacked from a very young age, and be forced to learn how to use food solely as a tool to control your body. It is not a lifestyle I would wish on any child. If families need access to better food (and they do), let’s focus on addressing that actual problem, and not continue to fixate on the “willpower” of the individual to control their weight. It’s misguided and harmful.

If you want to learn more about the science of weight loss and dieting, and how harmful it is, read Health at Every Size by Linda Bacon. We need to start collectively resisting these dominant narratives that connect body weight to health and personal worth. Body weight is an arbitrary physical attribute that is not an indicator of health or personal worth. Everyone should have the right to a healthy environment, and everyone should know that they have inherent worth, full stop, regardless of anything else, especially physical traits.

On Reading and Anhedonia

I have been sitting on this post for a few weeks now, as I have been battling a depressive episode. It caused me to forget my #1 rule about this blog: that I would post first-draft material that I wouldn’t nitpick over. The post doesn’t capture everything I’d like to say about its topic, but that’s not supposed to be the point here. So I’m posting it now, with a bit of a shove.

For the past few years I have been on a downward trajectory of cultural interest–and now it feels like I’ve pretty much bottomed out. It was probably inevitable. Eight years ago, in the middle of my PhD program, I was at the top of the curve. While I was reading every book, I was also watching all the TV shows, listening to all the “best albums of the year,” systematically watching the “best” movies, watching all the sports, and talking talking talking about all of it. It was a heady period of escapism in the midst of a brewing personal crisis. I didn’t know where my career/life was going, but I knew everything about your favorite ____ and could talk to you about it at length.

But as I finished grad school, depression set in. Health issues. Relationship issues. Trump. The pandemic. Climate disasters proliferated, inspiring a sense of imminent doom. I became glued to my phone after years of resisting. Escapism became challenging and then impossible. My attention span evaporated. I grew bored and frustrated with everything.

Now, I probably won’t watch the hot new TV show. I only listen to music sporadically, and it’s always my old familiars. I have sworn off sports completely (for many, many reasons). I’m still watching movies to fill the evenings, but only out of habit. I rarely enjoy them. And finally, heartbreakingly, I can’t seem to read. Nothing holds my interest. Everything irritates me or bores me or disappoints me.

Night after night, I sit down to relax for the evening and scroll through the streaming apps. I ask myself, “What am I in the mood for?” The answer always seems to be: “Something lush and powerful, that will sweep me away and take me over completely! Something profound and thrilling and beautiful.” “Yeah sure. But what will I settle for?” is the inevitable follow up. Maybe an epic or an Austen adaptation instead.

I’m listless. I’m uninspired. My senses are deprived. I want a transcendent experience. But my time and attention span are short. I need a jolt, that will also last and last. That will get me through the days. Through the time that just unspools ahead of me. The currently available “content” is not up to the task. I need the equivalent of a pilgrimage, a psychedelic trip, a divine epiphany. Instead I’m watching the films everyone says to watch. And they do nothing for me.

This is not a plea for recommendations. I swear to you it won’t work. I’ve tried everything. It’s more than “a funk.” I’m contemplating joining a Buddhist nunnery, or building a shack by a pond. In high school my senior year English class voted me “Most likely to join an Amish community.” I laughed along but never understood the joke, because I never really saw myself clearly. But I guess they saw something like this coming.

In the title I used a big word you may not know. You may’ve thought, “She’s using this big word to show off how smart she is.” And yes, this is admittedly true. But I only learned this word last week. Anhedonia: the inability to experience pleasure. It is one of the primary signs of a depressive episode, or a depressive disorder generally. I have struggled with depression most of my life, and I have experienced lengths of time when it was difficult to enjoy experiences I usually enjoyed. And social anxiety, inhibition, and lack of good “joy role models” have generally made it challenging for me to experience pleasure or excitement. I was taught to be reserved, demonstrate self-control, suppress glee, enthusiasm, and even interest in things. To be interested in things: ugh, the epitome of the uncool. But while my depressive episodes come and go, the experience of anhedonia itself seems to have settled in deeper. I always feel it now.

For most of my life I thought the one thing that brings me the most pleasure in my life is reading. You could strand me on a deserted island, but if I had my favorite books (reliable sources of fresh water and protein), I would be perfectly content. I believed that I didn’t really need anything else: not family or friends, not sex, not meaningful work… Reading, I believed, was all I truly needed.

My current drought is making me question this long-held assumption. A truth I have never faced before is thus: I have actually used reading to avoid my life. When I was young I used reading to hide from my family. Lots of discontented kids do this. But I also used reading to hide from other forms of exploration and experimentation. I used reading to build walls to keep people out, and to keep the “real” world away from me. That was its primary use for me—not pleasure. Sure, there were many books I read and enjoyed, even loved. But that wasn’t what I needed reading for. I needed it to hide.

So it does make sense to me now that—in a new phase of life where I am both trying to resist escapism and feeling like escapism no longer works or appeals to me—reading seems to have lost its place in my life. And the same goes for my backup modes of escape: TV and movies. If it was never really about pleasure, but mostly about avoidance, then what am I doing? I don’t want to do that anymore.

But then I am left with a rather steep challenge. If what I want is to recenter my life around joy and pleasure, how do I do that when 1) depression makes it difficult for me to feel pleasure, 2) I am woefully unfamiliar with what brings me pleasure and how to recognize it, and 3) the lifelong habit of gravitating toward cultural consumption out of a mistaken urge toward pleasure is proving to be rather challenging to overcome. It being a pandemic and currently winter doesn’t help either. My avenues for experimentation feel very limited.

Because that’s what I need and crave: a phase of radical experimentation. Thus far, self-exploration has allowed me to shed aspects of myself that were primarily coping strategies or socially imposed. And that has been liberating. But I’m not sure yet what is left of me, and how to nurture it. I’d like to feel more whole, rather than threadbare. I’d like to fill my time with creativity and joy, but I don’t yet know how to do that.

I’m not starting totally from zero, though. There are a few sources of joy that I can rely on, that are not complicated by misuse. Kayaking. Gardening. Swimming. Those are three things that bring me uncomplicated pleasure. Everything else I’m familiar with is thorny. Food? Exercise? Sex? Cultural consumption? Social interaction? Ugh. All so very complicated. And of course, what I feel called to do: writing, making art—very emotionally complicated, and nearly socialized out of me. But I am resisting hard in this area, scratching and clawing my way back to creative experience.

There are also other possibilities for pleasure that remain unexplored. And, on top of this, I know that finding pleasure in doing things, experiencing things, is also about bringing a certain approach, attitude, perspective to them, and not just about finding the exact right things to do or experience. So I do know ways forward: to explore the unfamiliar, and to do the work to make familiar, complicated joys less complicated. It is possible that I will return to reading for enjoyment—if I want to, and if I can shift my approach from one of avoidance to one of curiosity and wonder.

I’ll close with an anecdote: Early in my PhD program, I eagerly met my future dissertation advisor in his office for a chat. He had one of those professor offices that was completely filled with books, but in his case the collection was “organized” in very overwhelming and structurally unsound way. (A fire marshal had clearly never seen this room.) He sat in a broken armchair in the midst of this book madness, wearily scrolling on his laptop. I sat down across from him and his eyes went to my messenger bag, where I had a few pins secured to the front. One of those pins said, “Reading is Sexy.” His eyes lifted to meet mine. “Reading is NOT sexy,” he said in a voice that contained the weariness of decades of scholarly study. It was not dismissive or patronizing. It communicated his despair. This was probably the first in a series of moments that led me NOT to choose the career path he had. I didn’t want to feel that way about reading. But a decade and one PhD later, I kinda do. I still find the sight of an attractive person reading a book, and not just scrolling on their phone, very sexy. But if the act of reading ever felt exciting, alluring, radical, or sexy to me (and I can think of times when it did), that relationship to reading now feels very remote. It’s really no wonder when I consider the mechanical, unnatural reading practices I had to adopt during the PhD—when you’re basically expected to have read and formed a sophisticated and unique theoretical model on every book ever. It’s certainly no wonder if I seem to need a break of a decade or so from reading practice, as I completely reorient myself toward the act. In the meantime, I am hoping that cultural creation, rather than consumption, will help to renew me.

My ASD Diagnosis

This week I thought I’d write about what led me to seek an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) diagnosis. The short version is that it happened because I read Katherine May‘s Wintering. But that lacks context.

I pursued my diagnosis in 2021, at the culmination of a years-long existential meltdown. I’m not exactly sure when the meltdown started. Maybe at the end of my PhD program, when I stepped off the brutalizing academic treadmill into an unstructured and undefined future. Maybe before that. I know now, with the benefit of hindsight, that after the program I was completely adrift, depressed, and sometimes suicidal. But I was going through the motions and not confronting this at all. My partner at the time knew that something was very wrong. He started confronting me, and gradually it all came out. At first I just admitted that we had some relationship issues to work on. But he could tell that wasn’t really the core problem, so he kept digging. After a while I admitted to being depressed. We discussed it as a contextual thing, really post-PhD related. But in talking about my depression, and trying different things to alleviate it, we discovered that my depression was not really contextual. At least not at a superficial level. It wasn’t alleviated by exercise, writing, eating better, sleeping better… There was something at work in a deeper place, and it was sabotaging all of my attempts to feel better.

I eventually realized what it was. At first it looked like a total ambivalence and disinterest in everything. Alienation, disconnection. But underneath that, what I found was rage. White hot rage, directed at seemingly everything. I was controlling it only through avoidance and disconnection from everything. I was filled with rage at …. something… but I had found a way to contain and carry that rage in a vessel that looked like disinterest. Like a, “Fuck it all, I don’t care anymore. I give up.”

At this point in the process I was in talk therapy, and my therapist helped me uncover what some of the rage was about. At a very fundamental level, I did not feel like myself. It wasn’t just that I didn’t like myself, or know myself very well–it was that I literally didn’t recognize myself or feel like I understood myself at all. I looked at my life and it felt like it belonged to someone else. It was so much like the Talking Heads song, “Once in a Lifetime”: How did I get here? Whose life is this? Where is my life? The life I am supposed to be living? It felt like that life had been taken from me–that I had been taken from me. But I didn’t yet understand why I felt this way. I just knew that it was the source of my rage, and understanding it was the way forward.

It was in this context that I read Katherine May’s Wintering. My best friend recommended it to me, recognizing that the book describes a life phase that I was maybe in the midst of: one of sitting with and confronting the end of things, before new paths forward can emerge. It was affirming. But that was not what interested me most about the book. Instead, I became fixated on May’s descriptions of how she experiences the world at a sensory level–particularly after she reveals that she had recently been diagnosed with ASD. I remember thinking, “She experiences the world like I do. And she has ASD. Huh.”

I started reading about autism in girls, and how psychiatry is beginning to understand it better–and how it can differ in the ways it manifests in girls and boys. I had had a particular idea of what autism was, even in girls (mostly based on Temple Grandin), but I began to relax that understanding to include the experiences of other autistic women I was reading about. And I finally began to understand many of my own experiences, totally mystifying before but clearer now within the context of undiagnosed ASD or neurodivergence. It was revelatory but also shocking. It was like the optometrist switching between Lens 1 and Lens 2, if Lens 1 was severe astigmatism, nearly nonsensical, while Lens 2 was 4K Ultra HD. A thousand things about me suddenly made more sense. I went from a person who didn’t understand herself at all–despite being 40 years old–to a person who finally had some self-clarity.

And I understand now why it feels like, at some point, my life became someone else’s life, and I became someone else who never really felt like “me.” The person I was supposed to be, the life I was supposed to have, was taken from me. From a very young age I faced relentless, ubiquitous pressure from all sides to become someone else, to give up on my dreams, to live a life very different from the one I would choose. And that pressure had succeeded. I had lost, not even realizing what I’d lost until decades later. Of course I was filled with rage; who wouldn’t be?

As horrible as it has been, the pandemic has allowed me the flexibility to make dramatic changes in my life in the wake of these realizations. It has given me the ability to stop, turn around, and try to find my way back to the path I want to be on. Right now I feel closer to my real life, my real self, than I have since I was very young. And that feels both scary and really good. I don’t want to die anymore. I want to live, and keep getting closer. I know that I’ll never be the specific person that I would’ve been, if I’d grown up in a truly supportive environment and society. But I’m optimistic that I can recover enough of that person to integrate her with the person I’ve become, into someone who can feel fulfilled and maybe even love herself.

I know a number of people my age, particularly women, who are also currently exploring whether neurodivergence/undiagnosed ASD explains their life experiences. Some of them have approached me asking similar questions: How did I go about getting my diagnosis? Why did I get the diagnosis in the first place, if the only real result is self-knowledge, and not treatment or services–which are not really available for adults with ASD at this point. (We’re only now starting to confront, as a society, the fact that ASD isn’t confined to childhood, and it has profound effects on the adults those children become.) So I want to share my reasons and the process for getting my diagnosis, in case it helps others.

In terms of my motivation for getting a diagnosis: I was raised by a side of my family that had an unhealthy inner culture of self-diagnosis, hypochondria, and pseudoscientific beliefs. I have been making real progress in recognizing and confronting this, and the effect it has had on me, in recent years. And because of it, I knew that I needed an official medical diagnosis. I wasn’t going to be confident claiming ASD as part of my identity without the certainty of a medical doctor’s confirmation. So I found a Harvard-trained clinical psychiatrist who specializes in ASD.

After taking assessments and talking to her for a couple hours, she verbally diagnosed me with ASD. She also diagnosed me with ADHD; she says that these conditions often manifest together. (That has been a whole other revelation to me, one that I am also still processing.) I had to pay for her diagnosis out-of-pocket, because my mental health insurance would not cover it. But it was worth it to me, because I felt I needed to know for sure. And now I can process this self-knowledge in talk therapy at the very least, and maybe eventually there will be more resources available (and covered) for neurodivergent adults. I also know that I was lucky to have the means to answer this important question about myself. I recognize that not everyone who is contemplating neurodivergence/ASD as part of their identity has access to, or even cares about receiving, a medical diagnosis. But it mattered to me, and I was privileged enough to be able to access it.

As I expressed earlier, I felt profound pressure to learn how to pass when I was a child. I am also high-functioning, and a pathological people-pleaser. So it may be difficult for people in my life to tell how ASD is affecting me. What does my ASD look like? In a nutshell, a lifelong struggle with seemingly-inexplicable social norms and unspoken customs/expectations; misinterpreting social situations; not having a “filter”; interpreting everything literally; difficulty with certain types of humor; being quick to sensory overload; hyperfixation on certain personal interests; relying on particular bodily tics to comfort myself and maintain focus (i.e., “stimming”); a strong belief in justice and fairness that seems to exceed those around me; and a seemingly ever-present frustration and sometimes rage at feeling like I just don’t understand other people.

At this point in the process, I am focusing primarily on trying to unmask and feel more like myself–whoever that is. It remains maddeningly difficult to know who I “really am.” Partly because I’m not sure I even believe in a static, stable self that can be “discovered” or “known.” But also because I tried for so very long to hide (kill, really) the person I started out being. Most days it feels like my “original” self is just gone, and all that’s left is the messy shell of a person I constructed to hide her. I don’t know if it’s really possible to access her again, let alone invite her to take the reins. But I have optimistic days. And thankfully I have video of her, from our home movies now digitized. I have about 30 precious minutes that I’ve watched over and over. She is always singing and saying things in low, funny voices in the background, drifting in and out of conversations while clearly moving in her own little world, wanting attention on her own terms, messy-haired and … familiar. Maybe she is still here, somewhere.

One of my hopes is that, through trying to write about her, I can coax her back into the world.

Homophobia and a Private Fandom

I’ve had one favorite band for nearly my whole life. But if you ask people in my life who it is, many of them wouldn’t know. I learned early to be a secretive fan, and like many things you learn early, I never really stopped. Why was it a secret? In a word, homophobia. The band? The Indigo Girls. “Lesbians?” you might ask. “Who cares about you liking the folk music of two lesbians?” Welcome to growing up in the rural Midwest.

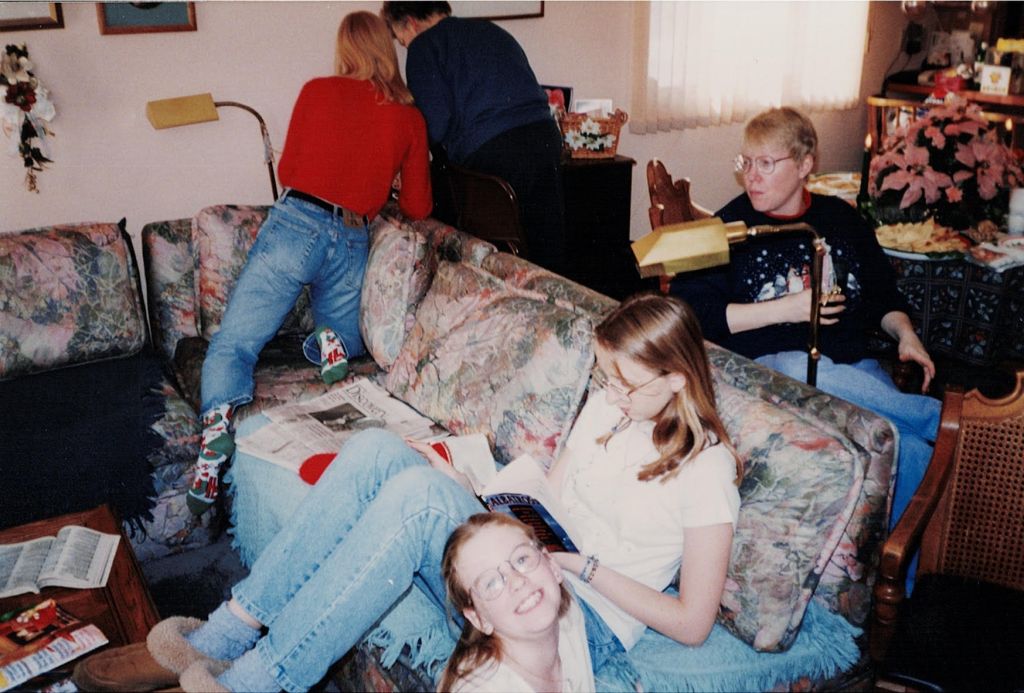

It was 1992. I was eleven. Someone made a cassette tape copy of the new Indigo Girls record “Rites of Passage” and sent it to my mother, who started listening to it in the car as she ran us around town, took us to the lake or our grandparents’ house. We always sang in the car–my mother, my sister, and me. We listened to the radio, but mostly we listened to my mother’s cassette tapes. Bonnie Raitt. Anita Baker. K. D. Lang. Linda Ronstadt. Tracy Chapman. But “Rites of Passage” was a different experience for me. I became interested in a way that I wasn’t interested in the others–like it was a special puzzle meant for me to decipher. “Are these men or women singing?” I remember asking early on. I’d asked the same question about Tracy Chapman. The female singers on the radio–Mariah Carey, Madonna, Amy Grant–sounded feminine. But the women on these tapes were … different. Their voices were lower, stranger, and weren’t sweet, pretty, cute, flirty, or enticing. Sometimes they were angry. Sad. Or enticing but in a lower register, which felt … different.

I eventually stole my mother’s copy of “Rites of Passage,” and kept it until I bought my own. I listened to it on my Walkman everywhere I went, and whenever I was alone in my room. Even on family vacations I would stay up late into the night, listening when everyone else was asleep. I knew every word. And I loved singing along to this record particularly, when I was able to. I liked listening all the way through singing the Emily lines of the songs, in Emily’s register, and then again singing the Amy lines of the songs, in Amy’s register. It was deeply comforting in a way that nothing else was.

I tried introducing the record to my childhood best friend. She didn’t seem particularly interested. Then one day she told me, “My mom says I can’t listen to that tape, and you shouldn’t either. They’re perverts.” I felt my stomach fall to the ground. I couldn’t process what she’d said right away, but I knew she’d said That Word. And connected That Word to a thing I loved. I felt something that I’d felt before, and would feel very, very often in my youth: terror at the possibility that I was being perceived as a pervert. I wasn’t even sure what a pervert was, but I knew it was the absolute worst thing someone could be. “I didn’t know that,” I said weakly.

I went home and asked my mother, “Are the Indigo Girls perverts?” She frowned at me and I told her what had happened. She sighed. “No, they are not ‘perverts.’ The two women in the Indigo Girls are lesbians. That means they love women, have relationships with women, have sex with women–instead of men.” And while this wasn’t the first time I’d been introduced to the concept of lesbianism, it was a shock that I finally “knew” lesbians, and that they had come to mean a lot to me without my knowing this seemingly important piece of information. I admit that I felt despair in that moment, and disappointment in Emily and Amy, like they’d let me down and made me vulnerable to attack. I think I felt tricked.

“How do you feel about that?” I remember my mom asking. “I don’t know,” I said honestly. “Well, think about it,” she said, and moved on to something else. And I did think about it. I tried not to listen to them. I tried to associate them in my mind with perversion, like my friends would. I believed that the most important thing in the world was for my friends and classmates to like me, and not think bad things about me. I also have many conservative family members, and I knew they would reject and distance themselves from me for liking them too. But I also cared too much about the record to stop listening to it. After a week or two I talked to my mom about my conundrum. Her fateful words: “You don’t have to tell people you listen to them, or talk about them with your friends. It can just be your personal thing.”

So that’s what I did. Middle school came and went. I saved up money for their new records, and listened to them constantly when I was alone. I never discussed them with friends or family other than my mom and sister, and I never took the cassette or cd cases with me anywhere. I just hoped no one would look at what was in my music player. I had long bus rides to and from school, and I sat against the window looking out and listening, trying not to mouth the words. In high school this continued. I made an effort to become a fan of other bands my friends liked. And while I did have a genuine appreciation for some of those bands, it wasn’t remotely the same thing. And it never has been, with any other band.

You might be thinking: “This level of concealment seems like a bit of an overreaction. What’s the worst that would’ve happened if people had seen your Indigo Girls tapes? They would’ve made fun of you? Called you a lesbian? Called you a pervert? Those are just words. Couldn’t you stand up to them?” And the answer is no. Absolutely not. It was already bad enough, being the person they saw me for. Adding this to the picture would’ve annihilated any ability I had to continue “flying under the radar.”

I mean, I was a dork. I was extremely emotionally sensitive, and although I tried so, so hard to hide it I never could. I was a walking open wound, and it was obvious. I was painfully shy but tried to overcome it through nervous talking. Every emotion I had flashed clearly across my face at every moment. Embarrassing me, making me feel angry but powerless, making me cry, was very easy. Boys would shove me down in the hallways, just to laugh. Slam my hand in my locker door. Trip me. Yank the collar of my shirt back. Shout horrible things about me in the hallways, to see my face turn red. I was terrified every day. And I was already getting called a “pervert”–but just at the normal amount that dorks were called perverts. I wanted to stay at that level of pervert-shaming. Because I saw what happened if you did or said anything to fuel “perversion” rumors.

For example, in high school two female athletes were seen kissing in the back of the team bus. The next day at school I watched as everyone around me seized on this information with eager loathing and ridicule. “That’s disgusting.” “She has always been crazy.” “I always knew she was a pervert. She tried to look down my shirt once.” “I can’t believe I’ve slept over at her house.” Looking back now, I find it hard to believe my memory: which is that the two girls were suspended from school and benched for the season. That can’t be true, logically–it is so extreme, even knowing what I know about my town. But even if it’s not true, it shows you the paranoid level at which I catalogued the event in my mind: Any act of lesbianism no matter how seemingly innocent would result not just in social ostracizing, but also systemic punishment and (it seemed at the time) lifelong consequences. From that time on they were forever (in high school years, at least) associated with that “incident,” and rejected by many of their lifelong friends. At least, this is how I remember it.

I grew up in a small rural town in a deeply red part of the state. There were no residents who were visibly out. My father believes that no gay people live there. I’m not sure what it’s like now (I got the hell out), but back then homophobia was in the water supply. The only synonyms for “gay” were “weak” and “perverted.” Anyone whose sexuality was remotely in question (I can think of a few teachers here, for example) had to go out of their way to either emphasize the heteronormativity of their marriages, or they lived very, very reclusively. When boys were beat up by other boys, they were always called “faggot” during the process. To allow yourself to be seen as even potentially gay was to invite physical and verbal violence upon yourself.

One funny thing about me and my experience in this context is: While I eventually came to identify as queer, I am not a “lesbian.” And back then I wasn’t even interested in sex, let alone whether it was with a supposed Group A or Group B. I was only interested in being liked and accepted, and being seen as liked and accepted. And whatever I could do to make that happen, I tried to do. I liked boys who were nice to me, which was a very rare thing. I don’t think I felt true sexual attraction toward anyone until college. I felt totally alone, alien, and was functioning at a survival level, trying not to get beat up, and trying to find friends who would accept me. I never did–at least not back then. But I had the Indigo Girls.